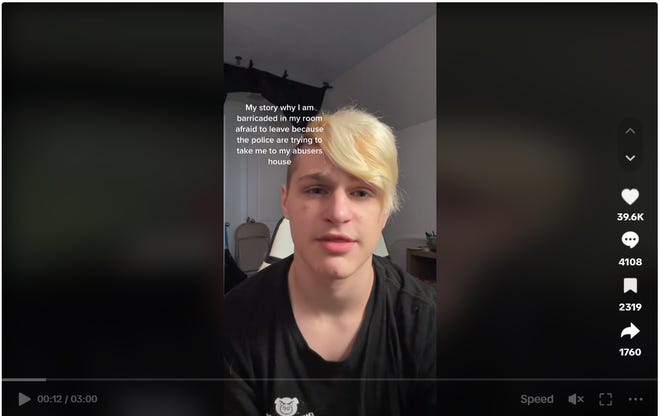

On the second day of a contentious custody battle that could have far-reaching consequences for survivors of abuse in family court, 16-year-old Ty Larson took the stand to testify to his own experience.

“He physically, mentally and sexually abused me from the ages of 3 to … 10 years old,” Ty told the court, referring to his biological father, Brent Larson. The abuse included “holding guns to my head, threatening me with hand grenades and touching me in my bed at night,” he said.

“If you could tell your father how he could help you… what would you tell him?” asked Steve Christensen, the attorney representing Jessica Zahrt, Ty's mother.

“Leave me alone until I’m 18,” Ty said. “I need to heal.”

The trial will determine whether Ty and his younger sister Brynlee Larson return to their father's care, despite both siblings claiming he abused them.

In 2018, the Utah Department of Children and Family Services reviewed the abuse allegations and found that they were confirmed. The Arizona Republic generally does not name victims of sexual abuse, but the siblings asked to be named to raise awareness of their case and advocate for other minors who find themselves in a similar situation. Zahrt supported this decision.

Larson, who testified Monday, denies the abuse and has argued in court that his children are victims of “parental alienation,” an unsupported psychological theory in which one parent accuses the other of brainwashing a child to to turn this child against him.

Larson has accused his ex-wife and the children's mother of launching a “campaign” of parental alienation against him. The theory is rejected as a mental disorder by psychiatric diagnostic bodies, including the American Psychiatric Association. According to experts who both defend and criticize parental alienation, the theory is used exclusively in the courtroom to refute allegations of abuse.

Custody disputes are not a “reason to discredit children’s statements”

Cassandra Walker, a state social worker who handled the siblings' case, said when asked by Larson's attorney that a difficult divorce would not cause her to doubt a child's abuse allegations.

“When parents are involved in a high-conflict divorce, does that raise concerns about the credibility of the children?” said Ron Wilkinson, Larson's attorney.

“I don’t question the credibility of children unless there is a specific reason for it,” Walker responded. “I wouldn’t look at a custody situation as a reason to discredit what kids are saying.”

Walker also clarified that the lack of criminal charges has no bearing on whether the state agency reasonably determines that abuse occurred. Earlier this year, several special victim prosecutors examined the case and concluded that the available evidence did not support a reasonable likelihood of conviction.

In a June letter explaining the decision, Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill wrote that the decision not to prosecute “should not be construed as a judgment on the underlying allegations.”

Monica Christy, a clinical psychologist who served as the family's custody evaluator in 2020, took the stand to explain her reservations about Larson gaining custody of the children.

“Obviously I didn’t want the children to be in a custody arrangement where they were in danger. So that was a big factor,” she testified. “I looked at what their experiences were from their perspective and whether or not they felt like they had been hurt, and that was the case in a variety of ways.”

She remembered Ty talking about how “his father would pet him when they went to bed” and what his father would do to “scare him or make him afraid of things.” She recalled that Brynlee “held on to being upset about the things he had done to her.”

Wilkinson repeatedly objected to her testimony and questioned the reliability of an expert who interviewed the children four years ago.

Christy said that when she examined Ty four years ago, giving custody to his father would not have resolved the conflict between them.

“The answer is no,” she said in response to the mother’s lawyer’s question.

Christy further testified that she had “no evidence” that other people were telling the children what to say or “instructing them in any way.”

“Are the children apparently legitimately afraid of what they have described to you?” asked Christensen.

“Yes, they did,” Christy replied.

She said she didn't believe Zahrt was to blame for not encouraging the children's relationship with their father, as Larson had argued.

“I think the children's feelings came from her own experiences, it wasn't that she was pushing them to reject their father. And it had more to do with her experiences and him than with her.”

“I want to live with my mother”

Ty testified that his mother “tried everything in her power” to maintain a relationship with his biological father, including providing him with a phone to call and text Larson.

He said he had written to his father “more times than I can count” and that he had received “no response at all.” Not a single answer.”

In his statement, Ty described his mother's home as “very bright” and “very safe.”

“I feel like I can actually rest when I'm in her house… I can be myself. I can invite friends. I can actually do whatever I want and express myself in my creative way. And I feel like I’m loved the most.”

“I want to live with my mom,” Ty said. “Because my father abused me when I was a child. And my mother was always there for me and never did anything bad to me. And always supported me in everything I ever did.”

Hannah Dreyfus is an investigative reporter for The Arizona Republic. You can reach her at hannah.dreyfus@arizonarepublic.com.

Comments are closed.