MIAMI – In the final days of this year's legislative session, Florida lawmakers and advocacy groups are pushing for an overhaul of the state's alimony law to better reflect today's marriages and make the system less burdensome on the alimony payer.

Florida is joining a grassroots movement in a growing number of states aimed at rewriting alimony laws by cutting lifetime alimony payments and easing the financial hardship facing some payers – still mostly men. Activists say laws in several states, including Florida, unfairly favor women and do not take into account the fact that the majority of women are employed and nearly a third have college degrees.

The Florida House of Representatives recently passed a bill that would make awarding lifetime alimony more difficult and less burdensome on the payer and would exclude a new spouse's income when awarding payments in the event of remarriage. Attention turns to the Senate, where the companion bill is less far-reaching. Florida had already changed some provisions in child support law two years ago.

Traditionally, alimony was intended to prevent divorced women who did not work and were less educated from falling into poverty. According to this view, the woman's role was to raise children and run the household. Today, when both spouses often work, this situation is much rarer. The question now is: What is fair maintenance in the 21st century?

“I think my parents, and certainly their parents, had far fewer women in the workforce,” said state Rep. Ritch Workman, a Melbourne Republican who is sponsoring the House bill. “The idea of a woman entering the workforce after 15 years of marriage and surviving on her own was ridiculous. It was the ex-husband's duty to support her until she found another husband. I'm sure it's an insult to today's women that they have to move from one husband to another for support. It’s not misogynistic to say that out loud.”

Last year, lawmakers in Massachusetts, which had some of the country's most outdated child support laws, passed a measure without opposition to rewrite the laws to make them fairer, following the recommendations of a select committee. The changes in Massachusetts, supported by the state bar association and women's groups, have prompted alimony payers in other states to organize and begin lobbying lawmakers.

In New Jersey, a resolution calling for the creation of a similar commission to study the state's child support laws has gained momentum. Connecticut lawmakers are currently working on a child support bill. The hearings are expected next month, lobbyists said. And in Arkansas, the Carolinas, Oregon, West Virginia and other states, activists are forming “alimony reform” groups, collecting stories about the hardships of long-term alimony and presenting them to lawmakers.

Because laws vary widely from state to state and give judges wide discretion with few guidelines, alimony rulings vary widely, sometimes within the same jurisdiction. In Florida, marriages lasting longer than 20 years typically trigger lifetime alimony payments, but it is also not uncommon for the higher earner in shorter marriages to end up paying permanent alimony that spans decades and only after the payor's death the former spouse marries again.

Many payers find it difficult to reduce alimony even when circumstances and income change. Appeals are often lost. The high cost of legal representation can make it impossible to continue fighting in court. Payers say alimony payments should not deplete retirement savings, discourage women from working or remarrying, or reduce a new spouse's income.

If living standards have to fall after a divorce, as they often do, the burden should be shared equally, they say. In Florida this is not always the case.

“It can strangle the person paying it,” said Alan Frisher, the founder of Florida Alimony Reform, an organization with 2,000 members, several of whom testified at recent legislative committee hearings. “Often we cannot afford maintenance at this level. It can prevent the recipient from ever working again, making more money, or marrying again. I don’t think anyone should be an indentured servant for the rest of their life.”

But Barry Finkel, a family law attorney in Fort Lauderdale, said the bill would lightly allow judges to exercise discretion.

“There is certainly a national trend against long-term alimony payments,” he said, “but the answer is not to create these obstacles and hurdles because there is an unhappy payer.”

Cynthia Hawkins DeBose, a law professor at Stetson University in Gulfport, said the bill and similar laws could address some inequities in permanent alimony payments, such as protecting a new spouse's income and ensuring that an ex-wife doesn't live in a $700,000 home while her husband lives in a $180,000 home. Former spouses, she said, should be allowed to move on and not be tied to each other forever.

“Overall, I have mixed opinions on this,” she said. “I don’t think alimony should be a welfare measure for the middle class, but I’m worried about the tail wagging the dog.”

In Florida, like most states, the child support system works mostly as it should. Ninety-five percent of those who divorce settle out of court, and judges often make fair decisions, legal experts say.

David L. Manz, chairman of the Florida Bar Family Law Section, said his organization opposes the House bill because it is too loosely worded and would eliminate too much judicial discretion. By addressing the plight of a small number of men, Manz said, the bill could end up putting more divorced women at risk. He said he was negotiating to change parts of the bill.

Even today, Mr. Manz said, divorce is more likely to harm women. They are still the ones who typically quit their jobs to focus on raising children. Even if they don't quit their jobs, their child-rearing responsibilities can affect their careers. Returning to work after a long absence is difficult.

“For every man, there is a wife or ex-wife who lost out,” Mr. Manz said. “Look at the standard of living of most people in long-term marriages: the standard of living of divorced men increases, while that of women decreases. This happens every day.”

“We are not in favor of disenfranchising someone who has given up their career,” he added. “What you’re hearing is a very vocal and persuasive minority.”

The men and few women in Florida Alimony Reform agree that they are a minority. But they say the injustice in the system is no less shocking. They say that judges' attempts to follow the law and maintain the same standard of living for a married couple after a divorce are mathematically impossible. It is said that former wives often benefit from this.

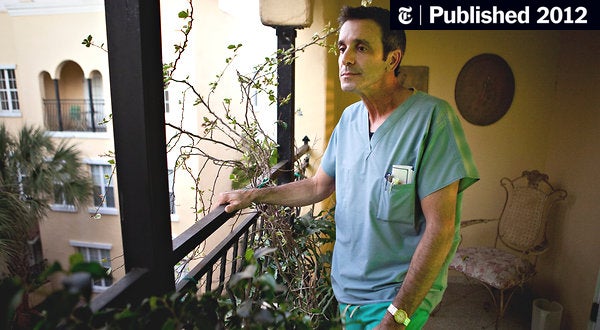

Dr. Jose A. Aleman-Gomez, a Cape Coral cardiologist who was married for 21 years, said he had to pay his ex-wife, a practicing dentist with a solid income, $50,000 a year, or about 25 percent of his salary . And Dr. Bernard R. Perez, a Tampa eye surgeon with throat cancer who was married for 20 years, said he was ordered to pay his former wife 85 percent of his income; He has been living in his brother's garage for three years and is on the verge of bankruptcy, he said.

Each man was also ordered by the court to take out a life insurance policy naming his former wife as the sole beneficiary.

The injured men say they are not against maintenance payments. They refuse maintenance payments with no end in sight. In their view, maintenance should be granted until the former spouse can complete training, find a decent job or return to work, or, if both spouses agree, until the children reach a certain age. The Florida bill would allow exceptions, such as for older women who cannot easily find decent jobs.

“I maintain their standard of living, but not mine,” said Dr. Aleman-Gomez about his former wife. He said he would pay off $70,000 in legal fees. “A person with a doctorate and a six-figure income shouldn’t be receiving alimony,” he said. “Alimony is for the people who need it.”

Comments are closed.